"I've been really bad"

Shame can dampen our hopes of change by making us feel not worthy. But there is hope.

One of the most common things I’ve heard when people come in for their diabetes check is this "I've been really bad" or "I've been really naughty".

I usually try and explore what’s behind this with people. Usually, I find that there’s a shame issue, and then look to help people challenge it because it can be so powerful and so destructive to relationships and fulfilment.

Shame…is the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging - Brené Brown

Shame makes us feel inadequate or inferior. It makes us want to hide or disappear. It disconnects us from others. With shame, we believe that we are bad.

Shame as a barrier

A lot of people with diabetes experience a sense of shame – maybe just because they have a physical condition, or because they’ve tried to get blood sugar down and feel like they’ve failed, or because they’ve tried a number of ways to get weight down and haven’t succeeded or because they perceive they’ve caused it themselves, by their behaviour or it’s seen in their community/culture as being a weakness.

Shame is surprisingly common, and it often shows itself in our self-talk:

“I’m not: good / pretty / talented / successful / rich / tough / caring / skinny / creative / popular enough.”

We’ve probably all felt those sorts of feelings at some point, particularly if we’ve had negative experiences previously – whether it’s bullying, excessive criticism from parents or abusive relationships.

We’re afraid that people won’t like us if they know the truth about who we are, where we come from, what we believe, how much we’re struggling.

Shame corrodes the very part of us that believes we are capable of change - Brené Brown

Shame can get in the way of change because:

- We don’t believe that we are worth any better OR

- We try and cover up what we see as our flaws through unhelpful behaviours like being perfectionist, lying (including to ourselves), hiding from or blaming others.

Or this one, which quite often shows up:

Taking care of them is more important than taking care of me.

Of course, it’s great to consider other peoples’ needs, but not when you come to be at the bottom of the agenda and your health is damaged as a result.

The impact of shame

Here are seven ways that shame can impact us. Do you recognise any of these in yourself?

1. We avoid relationships, vulnerability and community. Shame can often make us hide and conceal ourselves from others[1]. We end up avoiding vulnerability and sharing our true selves from the world. This includes not sharing real issues with your clinical team.

2. We suppress our emotions. This is particularly common in women[2]. We feel ashamed of who we are (“I’m not ____ – fill in the blank – enough”), or of something that happened to us. We keep our thoughts and feelings wrapped up for fear that we’ll be hurt again.

3. We feel worthless, depressed or anxious. Shame is often a contributing factor in depression, anxiety and low self-esteem[3]. We end up living out a difficult emotional and mental battle every day.

4. We become perfectionist. We believe the lie that says: “If I can look perfect and do everything perfectly, I can avoid or minimise the painful feelings of blame, judgement and shame.” Of course, it’s impossible to be perfect, but we increasingly get addicted to the quest of looking or doing everything right in order to avoid the stress of feeling more shame. It becomes an ever-deepening whirlpool.

5. We avoid taking risks. Shame is sometimes seen as being “a defence against being devalued by others”[4]. We avoid making decisions or taking actions that could lead others to devalue us. This can lead to us in effect sabotaging ourselves to avoid all possible risk of failure, even when the risk is small.

6. We are more likely to relapse back into unhelpful patterns. Research shows for example that people who struggle with alcoholism are more likely to relapse back into drinking if they experience shame[5]. Again, we can sabotage our efforts to change because in our hearts we don’t believe that change or healing is possible. In doing so shame “corrodes the very part of us that believes we are capable of change”. It can be the very real and powerful reason why we choose not to take steps towards healing.

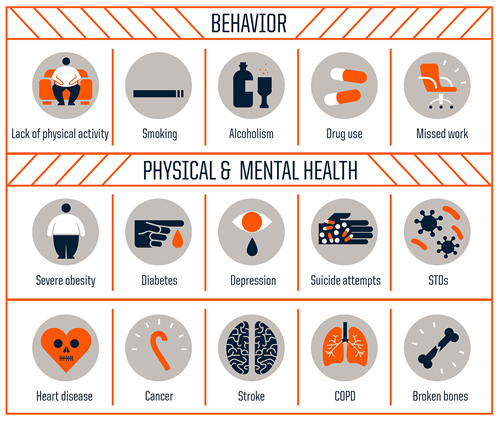

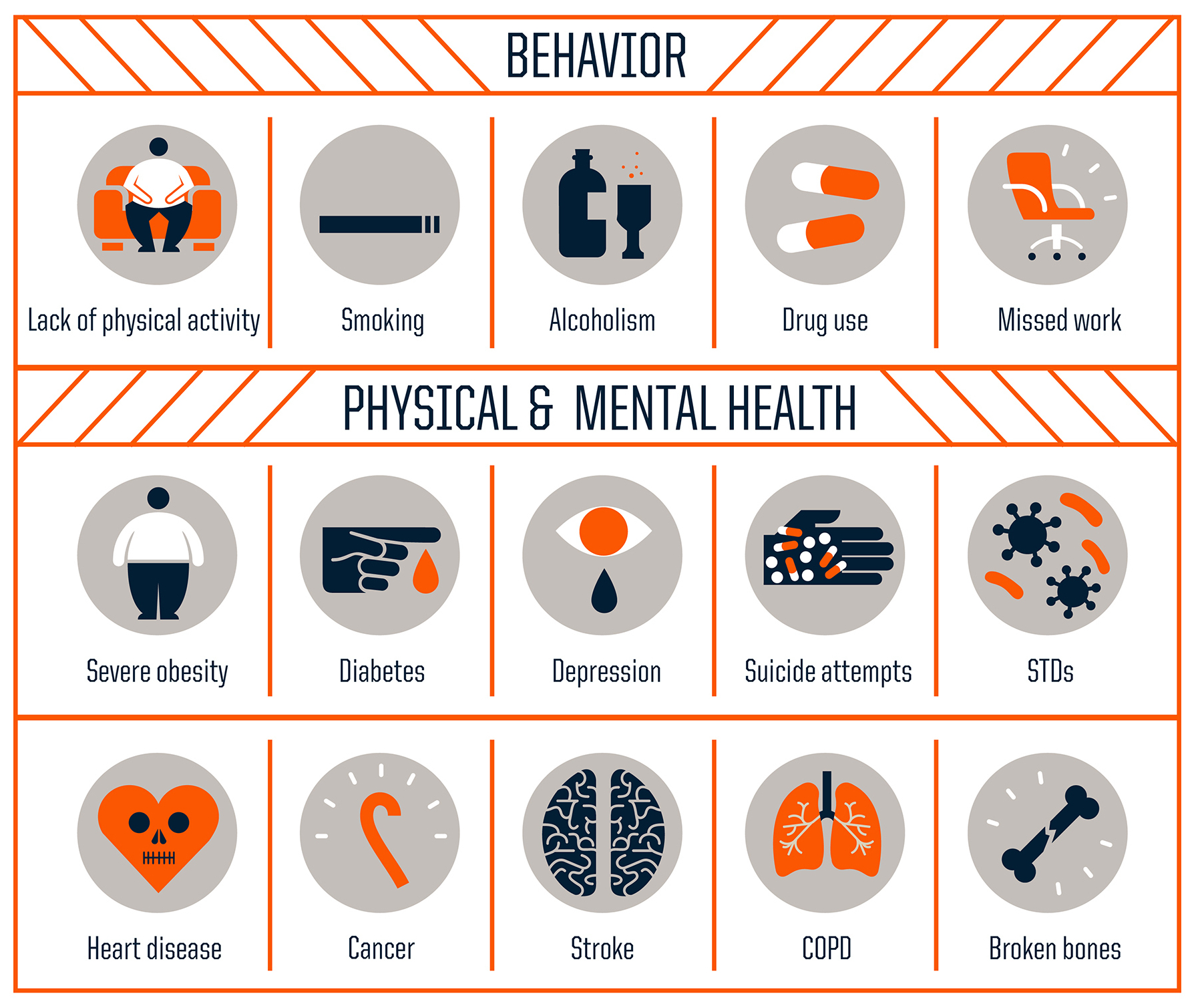

7. We treat ourselves as worthless because we believe we are worthless. This can live itself out in self-destructive behaviours that we know are bad for our health and wellbeing. We escape into addictions. We can end up on a path of disordered eating or of feeling bad about our bodies. Type 2 diabetes for some people is the result of years of self-destructive patterns of behaviour.

The roots of shame

There are a number of reasons people can develop feelings of shame, and it's important to remember that these reasons are often not our fault.

- Bullying. Bullying, for example at school, can set up patterns of fear, shame and low self-esteem.

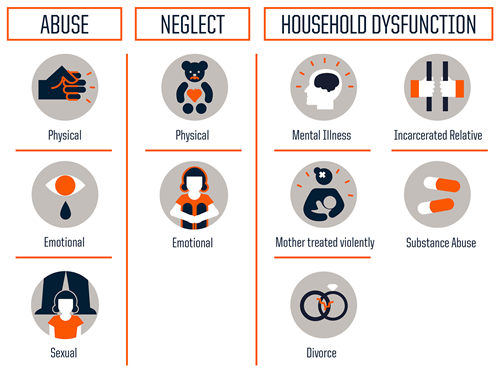

- Adverse childhood experiences. There is clear evidence[6] that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can have a significant contribution to shame. ACEs include abuse, neglect and household issues such as domestic violence and substance misuse.

Research has also shown a clear link between ACEs and the development of type 2 diabetes as well as other conditions. What researchers showed is that for each additional ACE, the risk of type 2 diabetes went up by 11%[7].

We can understand more about how ACEs can affect us by watching this video:

- Abusive relationships. This is common both as a result of the relationship itself, particularly where there is gaslighting involved, and as a result of victim-blaming and shaming that often occurs with domestic violence.

- Culture. In a shame culture, you know you are good or bad by what your community says about you, by whether it honours or excludes you. In a shame culture, social exclusion makes people feel they are bad, compared to a guilty culture where people think they’ve done bad things.

Breaking out of the shame prison

There are several ways we can develop the strength and confidence to begin breaking free of being imprisoned by our shame. Although it’s not our fault that we reached this place, doing something about it is within our power.

1. Recognise. When we’re in a shame spiral, one of the easiest ways of spotting it is that we get physical symptoms – these will often feel like panic.

2. Identify. Think about how we normally respond if we feel shame – Do we withdraw and move away from people? Do we move towards unhealthy relationships or do we try and people please? Do we move against others by becoming aggressive? Becoming aware of knee-jerk reactions increases our chances of learning to recognise specific shame triggers.

3. Share. Sharing our story and receiving empathy from others can help dissolve pain. That can be anxiety-inducing, especially if we’re sharing something we’ve never told anyone, such as abuse or neglect. So, choosing someone we trust is really important…and it’s best just to ask them to listen and not give advice. This might initially be someone like a health professional or a best friend.

Have a listen to what shame researcher Brené Brown has to say about vulnerability and shame:

4. Self-compassion. Self-compassion is about treating ourselves as we would a best friend. It’s about responding with care and love and concern to ourselves, just as we would to someone else in the same position. It can be helpful to just put our hand over our heart and wish ourselves well. It’ll be a small step forward.

This 30-second video might help us get into the mood:

5. Forgiveness. Forgiveness is a really powerful action that can free us from life imprisonment. Sometimes it’s ourselves that we need to forgive, recognising that we are more than the worst thing we have ever done. That ONE thing for which we feel we can never forgive ourselves, no matter how hard we try.

Forgiveness is to set a prisoner free and discover that the prisoner was you - Lewis Smedes

Sometimes there are other people we need to forgive. We recognise that we are more than the worst thing that has happened to us.

Forgiving does not erase the bitter past. A healed memory is not a deleted memory. Instead, forgiving what we cannot forget creates a new way to remember. We change the memory of our past into a hope for our future - Lewis Smedes

Moving forward

We’re all on a journey.

Shame affects many of us.

It can dampen our hopes of change by making us feel not worthy.

It can cause us to sabotage any attempts to change, often without realising that that’s what we are doing.

It can make us want to hide from the very thing that will help heal us – being vulnerable with safe people – and it can make us choose relationships that will cause us further harm.

But there is hope.

By taking some of the positive steps above, it’s possible to break out of the shame prison.

Getting help

If reading this has brought up painful memories, it’s worth seeking help. This may be through talking to a trusted friend or a member of your health care team. If you are feeling desperate or are struggling with the emotions this has raised then use one of the 24/7 mental health crisis lines:

If you live in Hammersmith & Fulham, Ealing or Hounslow call: 0800 328 4444

If you live in Brent, Hillingdon, Harrow, Kensington and Chelsea or Westminster call: 0800 0234 650

References

[1] Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J. & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345-372.

[2] Garofalo, C., Bottazzi, F. & Caretti, V. (2016). Faces of shame: Implications for self-esteem, emotion regulation, aggression, and well-being. Journal of Psychology, 151(2).

[3] Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety, and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 7(3), 174-189.

[4] Shame closely tracks the threat of devaluation by others, even across culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(10), 2625-2630.

[5] Randles, D. & Tracy, J. L. (2013). Nonverbal displays of shame predict relapse and declining health in recovering alcoholics. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(2).

[6] Wojcika K, Cox D, Kealy D. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and shame- and guilt-proneness: Examining the mediating roles of interpersonal problems in a community sample. Child abuse and neglect, 98, 104233.

[7] Deschênes S, Graham E, Kivimäki M, Schmitz N (2018). Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Risk of Diabetes: Examining the Roles of Depressive Symptoms and Cardiometabolic Dysregulations in the Whitehall II Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2018 Oct; 41(10): 2120-2126.